Ryan M. James

But I never specifically knew or had a plan of what I wanted to do, I just knew that I really liked stories, and my mother was a screenwriter. So, ever since I can remember, she was telling me about her scripts and I was reading them, and I was giving her notes that I felt that I totally knew what I was talking about [laughs]. And maybe sometimes they were good. She seemed to like it enough that years and years later, when we actually wrote a book and some screenplays together, she was into the idea that I could work with her.

So, I grew up around storytelling through all of that. I made a short film in high school, that wasn’t the stop-motion thing, and I was in theater and stuff. But it wasn’t really until right out of college when I finally majored in—they didn’t call it film, they called it media because they were teaching you at the TV studio they had. And I had to do film stuff and computer stuff. So, it was like a mixed thing.

It’s probably good we did that. I don’t think anyone who has asked to do that has done so out of ill intentions, but we actually put a lot of time and effort into figuring this thing out, so we’d like to see it through someday...if ever. That’s why we had the company formed, and I thought, “You know what? I kind of want to make a movie under that umbrella.” So, we made one after I finished college. And it was while I was working on it that I ended up at Pandemic doing testing stuff. The movie never went anywhere, but that’s really when the game stuff did.

While I was making those, I also took time (when the game finished and my contract was up) to film a whole bunch of footage that eventually made its way into the machinima (that I still haven’t finished releasing all the episodes for) called A Clone Apart. I had access to all these dev tools in the engine, so my brother and I (who was also a tester there) just did that. And then I transitioned at Pandemic into having a full time video editor role doing mostly their trailers and other stuff. Once in a while I did some cinematic related things, but it was mostly marketing.

So, the editing is the last step, right? I know how to write and I know how to direct on set, but ultimately all of that is irrelevant if it can’t be cut together in a competent way. Editing is that final stage of production where it all comes together, like they say. I had never edited anything before the really short film I made in high school, but we had some people, who worked in the film industry, that lived across the street. They offered to edit my film for free for me, so I learned with them how to edit in Media 100.

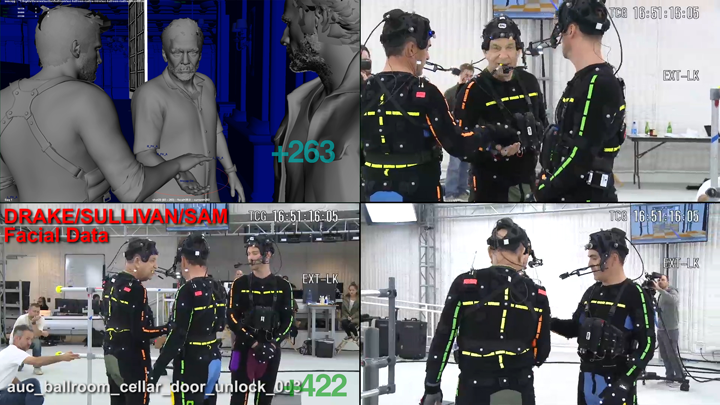

It eventually comes down to there’s a script and I look it over with whoever is going to be directing the mocap session. That way I understand what it is that they’re going for, including what subtext they see on certain lines or whatnot. So that I know to listen for that when we’re shooting. When I’m there on set, I have the script on an iPad. I’m usually notating down when I hear a take where the actor said that particular line, or part of a line, in a way that I think has the right emphasis to get across all of that subtext. So, when we bring it all back and I have to stitch a piece of dialogue to punch it up, then I can do that.

For instance, the actors might keep saying “tower,” but I need them to say “towers”. Then I can tell the director to have them take a wild take, which means the actors just stand still, don’t move and say the lines. And sometimes I’ll have them do that for part or all of the scene, because I need clean breathing or I need the word without any velcro or prop noise going on. Or it’s like, they said “tower” every time but, “Can you say it once and just say ‘towers’?” Then I’ll grab the “s” on that and cut it into whatever take we used. Little stuff, so I can patch the dialogue to make it clean later.

I know within my notes that the dialogue within this take is mostly fine, but these few lines are not right. So, I’ll change those right away at the beginning. Because we have the freedom with animation where we can use the dialogue from a different take. And because we’re capturing faces now, we can also take the facial motion capture reference video from that take and put it on there. So, I’m always trying to match the body performance, I’m not trying to have something that will feel disjointed. But sometimes they flub the line, or they said it better there, or they pronounced that thing in 13th century Latin better there. I’ll do a lot of swaps like that.

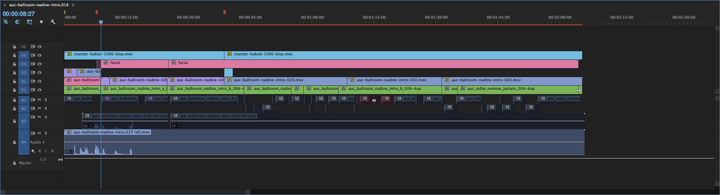

So, I’ll hand it to him fat. Then when the camera guy gives me cameras, then I’ll edit it down, actually take time out and give the scene some pacing. That’s when cinematography comes into play in the sense that we’re like, “We need to be on this shot for longer and basically stretch it out. They had this beat and then moved on, but we need to actually dovetail the action so that you have more time to take in what’s happening in this shot.”

And so I’m kind of like this funnel, where I’m there for the inception of everything, then I’m creating this proxy, and then I’m sending it out. Then I’m just kind of tracking it until it’s done and in the game. I’m kind of paying attention to these things throughout the whole of the process, even though what I actually have to do has to be done relatively early so that everybody else can make it look pretty. And sound pretty.

I became much more managerial in some ways. I still edited every cutscene, but I had help in tracking them and taking them to the end zone. I still listened to almost every line of dialogue that went into the single-player game. But I didn’t do as much on that, at least in the single player game. I didn’t cut as much of it this time or have as much input into it as I did on The Last of Us.

And there are little bits in the rest of the game that I got to do as well (in the single player). Anytime any of your buddies are with you, if you’re with Sully or Elena and there’s gameplay going on, they have different types of dialogue while you’re in combat, or if you’re lost, and stuff like that. So, I got to write what we call buckets of lines. Where it’s like, “Hey, what about this?” “Hey, look over there.” That kind of stuff. And trying to make all of that not terribly, terribly boring for the player. Stuff that’s helpful for you to hear and gives you information about what you need or what your situation is. You’re probably gonna hear it more than once, but you’re not gonna hear them repeated like, “Hey look over there. Hey look over there. Hey look over there.” You’re not gonna hear that, you’re gonna hear variations spread out through time. You may hear that line again, so it needs to be spread out and you don’t feel like you’re hearing repetitious systems. It feels natural. And so, I was doing a lot of stuff like that.

And so we have them, but we don’t have any specific place in the game to put them. And we don’t have a system that plays them, they’re really just this repository of lines that we have to fill things in. When design’s like, “Oh this thing has changed since you recorded it. We need to modify the line or we need to direct the player’s attention this way.” We can say, “Okay, well, we have this.” So, that’s a lot of what I do that isn’t directly related to what might be traditionally called a cinematic, but it’s part of what we do to make the whole game feel cinematic.

But sometimes it breaks. Like I remember in that same university level, Joel is talking with Ellie. And the guy who was playing it was crafting molotov cocktails. And it’s like, they’re having this emotional conversation and they’re crafting ammo. Oh well!

Then seeing what a man like that is capable of doing and willing to do for someone he cares about. I thought that that scene was great. It was brutal but, you understood (if we’ve done our job right). Because we’re always trying to make you feel the way the main character would be feeling. We want those to be in-line. So, if you are onboard with Joel, then you’ll be right there with him while he’s doing something pretty terrible to another person. It’s small, but I guess I liked how different that was from anything we had done before.

It’s organized chaos here because you don’t have someone just tracking those numbers and trying to keep the ship moving. But at the same time you also don’t have people whose sole job it is to keep the ship moving without understanding what is actually required. Like when I deal with producers at external studios, or in my previous job, they usually didn’t have the technical knowledge. They couldn’t answer you how long something would take. They would have to go and ask someone else and then they would come back to you. And if you remove that middle man, as long as the two people in charge (the person requesting the thing and the lead of the department) are up front about that kind of information and are on top of it, then you’re doing fine without having one more person who kind of all they are is like a messenger.

But it means it is on you and on that person to get up off your ass and go over and actually have that conversation, because you don’t have the messenger travelling between you. That is where you can’t be lazy, and sometimes all of us are lazy, and so things slip through and everything goes crazy. But having the more direct line of communication has always felt more efficient and a lot less frustrating.

It’s been very useful doing this. We have this long, unfinished screenplay. And when I say long, I mean like a screenplay is normally 120 pages because it’s meant to be a two-hour movie. We’re just using the screenplay format but we don’t intend to make it a movie, so it’s over that length. And the story’s not done because it’s just the format, so it’s like this big, open thing. I was like, “We might as well try and start snipping off this first section, as if it’s an episode, and publish it. And what does that take?” But it depends on where you go. Some places you’re like, “Yeah, I wrote this thing. Can you find me an artist?” And other places are like, “You need to show up with your whole art team and be ready to make a comic book all by yourself and then we’ll publish it for you.” And that’s an incredible amount of control, but that’s also an incredible amount of responsibility. And it’s very new to me.

In contrast, if you go to somewhere like Image Comics, which is very, very popular right now because they let the creators own everything, you still own the media rights and the character rights. They’re really just there as a publisher and they take their cut of the proceeds. But they’re just there as a channel and a vessel. That’s super cool, but they’re like, “You need to show up with your script about the cowboy, and with a sample issue with your artist drawing that story about the cowboy. We’ll tell you if we think your logo needs to be better. And we’ll give you editing suggestions and whatnot, but we want you to make your book. But you have to have your whole team together.”

It’s a huge and new world that I’m fascinated to try and get into, but I also know it may take a long time before it sees the light of day.

I was able to come in because I had games experience and I’d already kind of built up my skillset in my career at Pandemic. That’s how I was able to come here. Pandemic was where I kind of learned how to do a lot of stuff and how games are made. So, anyone who has a film background, and wants to get into that, should be doing that. Try being in QA and come in that way. Which is hard because of what someone might be doing already in their career. If they’re just starting out, like I was, that works great. If you actually have a job that pays well, well QA is not going to be very satisfying to you in that regard. But it is a good gateway.

I don’t think someone is gonna go and hire an editor like Stephen Mirrione, who’s won Oscars and stuff, to come in and edit their game. Because they’re just a person who knows how to make a film. They need someone who knows the tech.

Something that flat out saved our production on this last project was—you know how the Playstation 4 has a share button so it can capture video at all times—our co-president (he’s a programmer) made a thing. Because someone said off-hand, “Oh, this might be useful.” In like a day, he made something that you could capture video of the game, internally put it up like a YouTube video, add notes, and assign those notes to people. So that people could see, “Look, this thing’s broken here,” or, “Why is it this way?” Or, “Can you make this line of dialogue fire later?” Or, “Can we put a line in here that says this?” Or whatever it might be. So, we were constantly able to have fast, visual notes of the game in its exact state. And it was made in like a day by this guy.

The other thing I think is important is whoever you’re collaborating with, whether it’s an actor on the set or a co-writer or another editor or anything, context is so important. So being able to tell a person what you’re thinking and why you feel something should be the way it is. Being able to have discussions like that when collaborating. Or like telling an actor, “The reason this is is this way is because this happened earlier, and now this is where you are.” But it’s not just with an actor, you can do that whatever the situation is. Even if it’s going to a programmer and saying, “I really need this tool to be able to do this, because right now I’m doing these things and it takes ten hours. If you do this, it will take me one.” Just being able to give context to people is very, very important, both creatively and logistically.

Not everybody does that, and I’m not always good at it either. But it’s a big thing I try and keep in mind in everything I do because I really love collaborating with people. It’s the most crucial thing. As opposed to kind of locking off and only saying "no" to things and not being constructive. You need to give more information to people.