By Bailey Kalesti

- Interview recorded September 2016 -

Bailey:

Let's go way back. Where did you grow up?

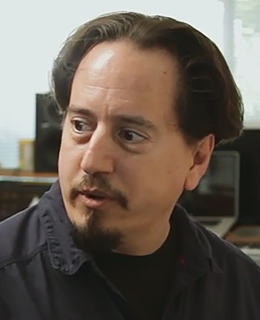

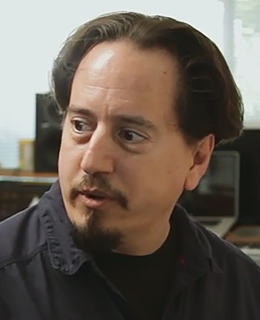

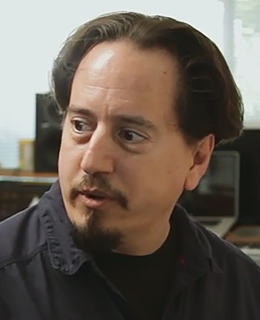

Derek Duke

Derek:

I'm from Southern California. I grew up in Huntington Beach, which is here in Orange County. Not too far from Blizzard. So, I was born and raised here, and I even went to school not too far from here. First a little stint at San Diego State, then I left there and went to CalArts.

Bailey:

And you were studying music at the time?

Derek:

Yeah, composition and world music.

Bailey:

Were your family creative types, or were you different from them?

Derek:

I was pretty different from them. My dad was a stockbroker and a politician. He was councilman and vice-mayor of Huntington Beach. And he was really into classical music. Although my brothers were not, he was. There were a few years, like in fifth and sixth grade, where he would pull me out of school one Friday a month to go up to LA to see the philharmonic, which was pretty formative. Although, it was definitely weird when I wanted to go to school for music. I would say he was definitely anti-supportive.

Derek:

It's not the kind of thing you could make money from. So, I think that old chestnut that a lot of kids go up against when dealing with their folks. I had wanted to go to CalArts out of school but my parents didn't want that. So, I went to San Diego State because it was a more normal school and I could major in music and get a more normal education. But it didn't jive with me, so I dropped out. Then I started writing music for dance and other things just on my own. I decided that I would just raise a lot of money, buy a bunch of synthesizers, and go to CalArts on my own dime without help from my folks. Just do whatever I had to do. So, that's how I got back to CalArts.

Bailey:

What kind of music were you writing?

Derek:

I guess it was minimalist or post-minimalist. It was definitely more academic. I wasn't interested in any way being a media composer. It was all music for modern dance. The main choreographer I worked with was a dance choreographer named Steve Paxton. At one point I did something for The Olympic Arts Festival while I was at CalArts when the Olympics were here in LA. But through my career, at CalArts, and being in academic music, there was still kind of this sideline because I had grown up playing video games and loving them. My dear friends, who I watched play chess on Saturday nights, didn't really have a high opinion of playing Moon Patrol in the cafeteria at school. There was kind of a push and pull there, and I think eventually, after school, a lot of academia was hard for me. Just how serious it took itself. I still love academia and I still love that music to death, but in the end it wasn't for me full-time. I found outlets in other ways.

So, because I was kind of doing this dual-degree (world music and composition), I wanted to give South Indian music a try after school. I had studied some North Indian music, but I didn't feel like I'd got in deep enough. I had done gamelan, West African music, and I had even traveled to West Africa. But I wanted to give South Indian music a try before I decided to devote some serious time to either North Indian or South Indian, because they're both very serious kinds of music. So, I tried South Indian music and it really, seriously captured me. My teacher’s visa expired, who I was studying with at the time. So, she had to go back to India. She told me, "Okay, why don't you come and live with me and study like a real student? Study full-time and I'll take care of you." So, I did that. I moved to India and lived there for about a year and a half, studying full-time.

Then I came back, was working, and then, after some time, that's when I got into interactive as a job with Virgin. That was about the time that CD-ROMs were big and America Online and all that kind of stuff was blooming. Diablo was out and there were rumors about orcs in space, and stuff like that. It was some time after that company went under, and I was patrolling the internet for gigs, that there was a posting where they were looking for zerg music. I sent an audition CD-ROM to Blizzard to try out for that. Glenn Stafford called me up and brought me in, and they asked me to do some music for the original StarCraft. So, that was the first gig and that was my first association with Blizzard as a contractor. Because at the time I was doing commercials, different cartoons, and whatnot. Then it was probably fix or six years later that I moved back down to be local that I actually came on full-time to Blizzard. We were working on Warcraft III and I think it was just about the time we were shipping Lord of Destruction.

Bailey:

Just to kind of jump back a little bit, what was it about South Indian music that captured you and inspired you to go to India and be part of that?

Derek:

It would be hard to say something about South Indian music without saying something about North Indian music. North Indian music, not to say that it's not sacred, but it is a secular music. South Indian music is sacred, meaning that every time a veena player is plucking the string or a violin player is rebowing the string, that's another syllable of a sacred text. There is no purely instrumental music. It's 100% sacred. Whereas North Indian music is instrumental. In western tradition, we have these symphonies which are for the glory of god, or whatever, but they're not directly tied to these sacred texts in the lyrical form.

So, my teacher was a singer and her eyes would roll back in her head as she would sing these incredible things. It was an experience. She would teach me these instrumental things and I would practice them. It was kind of like The Karate Kid. She would teach me these exercises and she would ask me to do something that I knew I wouldn't be able to do. And I would laugh, "Oh, I couldn't do that." She would say, "Sing this scale, in this meter, with this pattern." And I'd never practiced that before, but I would just do it. But it was because I'd practiced doing this other thing like five hundred times. Practicing that wax on, wax off kind of thing.

Anyway, so there was a lot of pulled me into that. Maybe it was just the right time. You have to be young enough and unattached enough to be able to say, "Oh, I'm going to India."

Bailey:

Yeah, you didn't have a family or anything yet.

Bailey:

So, have the kind of things you were doing there continued to influence what you create these days?

Derek:

Yeah, I think it does. But I also think there are elements inside of me that were there before I found that. If that makes sense? I remember I was so heavy into the West African music, and when people came to see my graduation recital, they were expecting that it was going to be all this rhythmical, big drums kind of thing. But it opened up with this 22-minute ambient thing for five graphite instruments going into tape loops. So, it was really long and ambient. And if you listen to music like in the Draenei starting area or Exodar, there are these long vocal loops. Or places like Skywall where you get that essence that time kind of stands still and stuff like that. It's certainly not in all the music that I do, but there are moments where that is allowed to seep into that in some of the Blizzard music.

"Azuremyst Isle." Composed by Derek Duke for World of Warcraft: The Burning Crusade.

Bailey:

I noticed that with the Reaper of Souls music. That was actually one of the first things where I was like, "Man, I need to know more about the people who worked on this." Just because I felt that it had a real, emotional complexity to it. In hearing what you're saying, I feel like it has some of your personality in it. Can you tell me a bit about your process for working on the Reaper of Souls score for the cinematic?

Derek:

Yeah, there's probably a little bit of the academic that got into that whole project. With Reaper, that was the first project at Blizzard where I was actually the music creative lead for the whole thing. So, that was pretty awesome. And it was great having a big enough lead time to be able to engage creatively with lots of people about what was going to be done. We basically started on that right after vanilla got shipped. I started working with Marc on that right after. He already had storyboards going and we sat and started thinking, "Okay, how is this going to go?" We started at least talking about stuff and sharing different scores back and forth. So, it wasn't just one person temping in this or that.

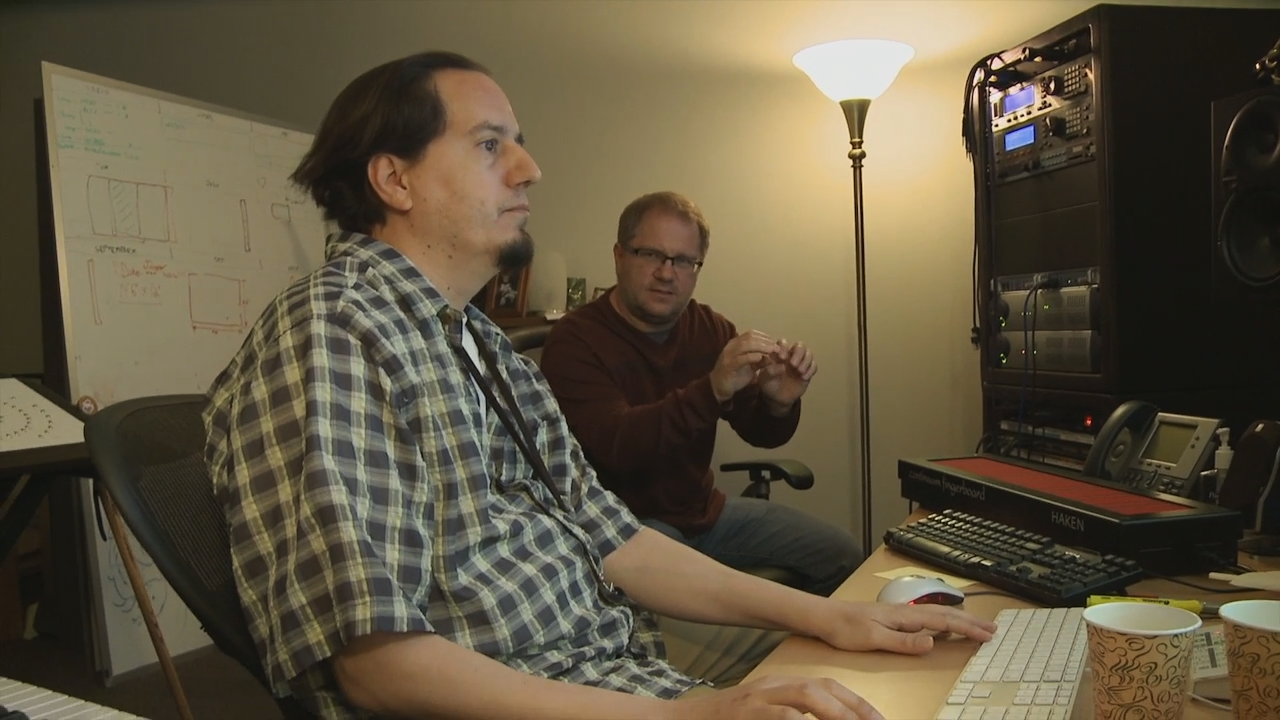

Derek Duke and Marc Messenger (cinematic director) working on The Shadow of Death.

The Shadow of Death, the intro cinematic for Diablo 3: Reaper of Souls.

The Shadow of Death, with the sound effects and vocal tracks removed to focus on the music.

Bailey:

Right. They were influencing each other.

Derek:

Right. And then another thing that was great was that before we had gotten too far, I had done a certain amount of first pass music for Reaper. Basically like, "Okay, these are gonna be some of the main themes, and this is kind of textually what we're going for." Like the whole thing with Malthael and the sacristy bells that I used. Things like that and the sound of the rubber ball on the timpani. And I knew that we wanted to do it in the church, and I knew that we wanted to do it on the stick. Meaning that I didn't want to do it to a click track. And then taking that music and being able to use that to bring into the movie while we were still working on it. So, then re-temping in that until we got up to finally scoring the thing at the end.

We were able to record our concept pieces and then put them together in parts of the cinematic to help us sell and flesh out what I was doing in that. Instead of just having to rely on the mock-up. Because a lot of times that's one of the challenges. Selling your ideas and what you're doing through the mock-up. And there were certainly some things in that particular cinematic that were really challenging.

For instance, the connective tissue from Malthael rising up and Tyrael coming down. So, there was actually a whole section where the bell is ringing and where the drums come in. We had been trying so many different ways of connecting that to the portion on the bridge. We had all these different horns and when we'd gone to record it, I recorded maybe four or five different types of connecting pieces of music to do it. Because we just hadn't found the satisfactory piece. At a certain point, we've committed to the date and the time, so there's kinda no turning back. So, we went up there and recorded it, and we came back and we were getting close to mix. I was in my office and I had the idea about using the big drums. So, I cut that in with the drums and the bells. I played it for one other person, and I really liked it. Then I brought Marc in and the reaction was, "Wow, that's really different." Because it wasn't what we had been working to. It was really, really drastically different. But ultimately everybody loved it, it works perfectly, and it's definitely the big, iconic moment.

Bailey:

Yeah, I think it worked. It had a lot of emotion to it. When you're preparing for recording with an orchestra, do you enjoy that process? Is it nerve-racking? Is it exciting?

Derek:

It's all of the above. We're almost always under tight time constraints, and there are so many elements that go into it. There are lot of people to wrangle, and it's never just about the notes. There are different kinds of sessions. There is music that's just for the game and there's music that's just for the cinematic or the cinematic projects. Those might be still waiting for their final approval or a timing change, so they might be waiting until the last minute so they can be locked and go off to the orchestrator. They might need to be printed out on the stage the day before we actually record. So, there's always a lot of unknowns with a lot of these things. So, it's never luxurious. It's always exciting, that's for sure. And it's always amazing. It's one of those things when you hear your samples and things that come out of our computers these days, it's amazing that they can make the sounds that they do. But when you get to a real stage and you just hear the musicians start to warm up, you're like, "Oh my god, now I know why this costs so much money." [laughs] You just realize what it's all about. I'm teasing about the money, but it's amazing what that humanity brings to it all. It's really amazing.

"Chains of Fate." Composed by Derek Duke for Diablo 3: Reaper of Souls.

Bailey:

To hear the sounds in that space.

Bailey:

It's usually a process that lasts for a few days, right?

Derek:

It depends on how much material we're trying to cover. What the project is. For example, for Overwatch we record less often for less amount of time.

Derek:

We're usually tackling an episode or two.

Bailey:

The animated shorts.

Bailey:

So, for Overwatch were you involved with the game music in addition to the cinematic work?

Derek:

Yeah, I function as the project music director and lead composer for both Team 3 [Diablo] and Team 4 [Overwatch]. That was kind of the big thing, after finishing Reaper, was jumping right onto Overwatch and sort of creating this whole new musical IP for Blizzard.

Bailey:

Yeah, it definitely has a different feel.

Derek:

Yeah, totally. So, that's been an amazing run. Those cinematics are pretty awesome in that, starting with the intro [Overwatch trailer], there's always been more than one composer involved in some way on each.

"We Are Overwatch." Composed by Neal Acree and Derek Duke for Overwatch.

Derek:

I like to think Overwatch is a team-based sport. We're stronger as a team and I think it's what helps create the best color. Neal Acree was the one who brought that intro cinematic to the stage, and put that all together, but it's built out of many things. One of the main themes was Sam Cardon's. And Chris Velasco had done this amazing horn arrangement, the fanfare. And I had done work on the piano section. So, we had four people on it. On another cinematic, we might have had help on the electronics from Jaroslav Beck, and me helping on something else, and Neal doing something else. Whatever it takes to get the best work for us all to get the most emotional impact for the story and the franchise. It just seems to work for that IP.

Bailey:

Right, everybody is bringing their own voice where it's needed. Did Jaroslav Beck do the fight scene in the Hero?

Derek:

Yes, he helped with that. Very good. And we worked together on Alive.

Bailey:

What's been really fun for you about Overwatch in addition to that additional collaboration?

Derek:

I think the most fun thing about it is spreading the wings in that way, and learning to give so much of it away. And that I really love electronics a lot, and being able to work with electronics a lot more freely. Electronics that aren't just dark. That aren't used in just a dark way. Electronics can be used in so many different and colorful ways. They can be bright and they can be happy. Especially in our times. The current generation is used to it. They grew up with synthesizers and there is no baggage.

So, they really have the potential to express any kind of emotion. It's really awesome. I have to catch myself when going back to the other franchises. Realizing that I have to kind of come back to those limitations, where I'm not as free to go there. Whereas with Overwatch it's all yours.

Bailey:

Right, you mean because Diablo is a much darker, more well-defined universe.

Bailey:

So, you're using these tools, like the electronic stuff. How do you go about deciding what you're going to do for a particular emotional quality? Is it just a lot of experimentation?

Derek:

If you listen to the kinds of music that have come out of the Overwatch cinematics and what music is in the game, you can kind of see the harmonic emotion in there. It's fairly simplistic and fairly open. Whereas fantasy music speaks another kind of harmonic language. The harmonic changes are a little different.

"A Tenuous Bond." Composed by Derek Duke for Diablo 3.

Derek:

When you simplify and strip down our music to just the chords, it's going to be very, very simple and almost like a pop song. If you simplify some of World of Warcraft's music, it would probably be less like a pop song and the chords would be a little more complicated. A little more dense. So, like the harmony would be more dense, but not super dense. The Overwatch music doesn't sound like fantasy or science-fiction, it sounds clear or clean. Again, it's knowing how to go there.

I have these checks that I go through when I'm working on something. And one of those things is, "Is it hopeful? Is it bright?" When you get down to it, can I hear--down deep inside of it--that hopefulness? Is it positive? Because that feeling is kind of one of the biggest internal things about the Overwatch franchise.

For example, when we started working on the We Are Overwatch piece, Jeff had temped it with music from a trailer. It was a descending minor line. It was intense and kind of sad or tragic. Because it starts with the guys trapped behind enemy lines before Pharah shoots up. He showed it to me and I loved the words to it. And I had this idea that I'd love to do a piece for the franchise sort of like the boy scout's creed. Where you have "Obedient," "Brave," and "Reverent." Where they're saying those things and then there's just this heroic music happening in the background. So, I wrote those chords and I did that mock-up. I had a meeting with Jeff Kaplan and I showed him, "Oh I'm working on this thing. Take a listen to that." And he's like, "Oh my god, you've got to play that for Jeff [Chamberlain]." So, that was that, and we started chasing that.

We Are Overwatch, the cinematic teaser for Overwatch.

So, my point being that it was piece that had that hope in it. I definitely changed the meaning of that piece a little bit, but that message of hope is that defining essence of the Overwatch franchise, at least for me. And that's the biggest check of the harmonic language or any idea that I come to or that I write. If it's trying to be a far off country or some different map, it has to sound that way in some sort of positive light.

Bailey:

I think that's pretty awesome. For each franchise, do you have a similar kind of check like that? A defined essence?

Derek:

I think with the other franchises, especially with the other guys too, we've been doing it so long that I think we all instinctively know what those feel like. It's less necessary, except when we've had to work with other folks. Which then just becomes a challenge for other folks. I think with World of Warcraft you've got some people who really learn to speak the language of that game. We have a lot of good WoW composers working with us now.

Bailey:

Makes sense. Over the course of your career, what has been one of your favorite projects or tracks that you've worked on?

Derek:

That's hard to say. I think there is lots of different WoW music that I really like. Like Skywall or the Draenei music. Those starting areas from the Draenei areas, just because they were kind of personal I suppose. "A Mortal Heart" from Reaper.

"A Mortal Heart." Composed by Derek Duke for Diablo 3: Reaper of Souls.

Bailey:

What was it about the Draenei starting area that was personal to you?

Derek:

I think it's maybe less personal, but I think just because it's vocal music. The beds of that were vocal. And I also think I was pretty successful in making some kind of new timbre. Music that didn't sound like any music we had heard before. I like those kinds of things. When you get to hear music that's otherworldly, but it doesn't sound electronic. There are the droney voices and different sounds in the background.

Bailey:

In a similar vein, is there anything these days that you've been trying to learn more of? Some new frontier that's been exciting you lately?

Derek:

Well, I devour music. I listen to and buy tons of music. That's something I never stopped doing. So, I always have backlogs of music to get around to listen to. I listen to a lot of electronic music. Like electronic drone music, electronic classical music, academic music, and film music. Just pretty much everything. So, I'm always looking for more stuff. And it just goes into the queue of getting around to listening to it. I buy and collect lots of scores and get around to studying those in my free time because I still like to do that. And I have big studio at home and I really like to play with electronic synthesizers, processing electronics, and things like that.

Bailey:

When you're at home doing that stuff, are you working on anything particular or are you just experimenting with stuff?

Derek:

Well, I try not to work at home, which I'm hoping to be more successful at. But yeah, usually it’s just personal. Just me doing my own experimenting. But if there are techniques that end up being useful at work, that's fine. But I'm not necessarily there creating new music to use at Blizzard.

Bailey:

I think that's cool. I think it's important to do something that's more for yourself. Have you worked on any personal tracks?

Derek:

I mean, I do record a lot of what I do when I'm noodling around, but I don't release what I do in any sense.

"Corruptors." Composed by Derek Duke, Glenn Stafford, and Neal Acree for StarCraft 2: Heart of the Swarm.

Bailey:

You were saying that you listen to a lot of music. Were there any particular musicians that you've been interested in or following the work of lately?

Derek:

If I just list the most recent acquisitions, would that help?

Derek:

Patten and then Helen Money.

Bailey:

What kind of music?

Derek:

Patten I think is like IDM. They're on Warp Records. Helen Money is like cellist, but goes from drone to like heavy metal, and then back to drone again. And another artist is Saåad, and that's kind of droney ambient with weird flutes on top. And then one more would be Koen Holtkamp, and that's synthesizer stuff.

Bailey:

Cool. Well Derek, thank you so much for taking time out of your day to speak with me today. It's been a great pleasure.

Derek:

Cool. It's good to meet ya.

Bailey:

Keep up the outstanding work, man. It's great stuff.

The views and opinions expressed in this interview are solely those of the people in this interview and do not necessarily reflect the views of their employers. This interview was recorded in September 2016.

Derek has generously shared a few more of the albums he has been listening to recently. You can listen to them on Spotify here:

Continuum by Paul Jebanasam

Continuum by Paul Jebanasam

Mason Bates: Works for Orchestra

Mason Bates: Works for Orchestra

Colliding Contours by Driftmachine

Colliding Contours by Driftmachine

The Revenant: OST by Ryuichi Sakamoto, Alva Noto, & Bryce Dessner

The Revenant: OST by Ryuichi Sakamoto, Alva Noto, & Bryce Dessner

Music of Morocco: Recorded by Paul Bowles, 1959

Music of Morocco: Recorded by Paul Bowles, 1959

Night Melody by Rival Consoles

Night Melody by Rival Consoles